Phenomenology

I am a liberation psychologist by training. I cultivated my knowledge and practice of liberation psychology at Pacifica Graduate Institute.

My dissertation was entitled Liberation from Corporate Psychic Colonization: New Subjectivity Awakening in Conscience.

One of the essential tools that I use in my work is phenomenology. Dutch psychiatrist J. H. van den Berg (1972) described it as a method and orientation and that the essence of phenomenology is fidelity to experience:

“He who desires to know what, in a given situation, is happening psychologically, does well to put himself in that situation. He should refrain from quickly pronouncing judgment on the situation, for a quick judgment is usually premature. First to describe, then to judge. To describe is the most important . . . the investigator adheres to the given facts. This is the basic principle of all phenomenology: the investigator remains true to the facts as they are happening”. (pp. 63-64)

Although phenomenology’s adamant commitment to subjectivity is an important shift from the supposedly neutral stance of the researcher, its loyalty to experience still has a tendency to create pitfalls that are similar to the creed of objectivity that is a foundation of empirical epistemology.

Professors Isaac Prilleltensky and Dennis Fox (1997) describe critical psychology as a discipline that challenges the theories of mainstream psychology taught in universities and practiced by researchers and clinicians, in terms of how they tend to maintain the existing power structure. Paul Ricoeur’s philosophy of phenomenological hermeneutics is meant to “embrace all phenomena of a textual order” (Kearney, 2004, p. 19). This is truly possible only when researchers first examine and take into consideration the power structures and the subtle biases manifested as dominant views within the sociopolitical context through which the phenomena emerge.

Events that occur in the world take place within a certain sociopolitical arrangement. Being true to the phenomena requires researchers to examine the cultural context through which their engagement in the pursuit of objective knowledge is made, and to become aware of the existence of power dynamics that produce oppression. Without this critical analysis, the researcher’s fidelity to the phenomena creates inadequate knowledge. Mainstream phenomenology and hermeneutics often do not examine hidden systematic injustice or bias embedded within the society from which the researcher hails and their phenomenological inquiry often only reinforces the status quo.

Prilleltensky (2003) puts forward two forms of validity that supports critical hermeneutics research. The first is called “epistemic psychopolitical validity,” which is to witness and assess the oppression that exists in society and the second is “transformative psychopolitical validity,” to move toward altering the existing situation toward liberation. Through epistemic psychopolitical validity, researchers first gain the understanding of the world presented as it is. What fundamentally differentiates critical hermeneutics and phenomenology from the traditional versions of these disciplines is Prilleltensky’s second path of validity.

Critical hermeneutics and phenomenology encourage researchers to critically examine the foundation; the social and political context through which phenomena emerge and also to not stop at the description stage, but examine ways to transform the observed situation.

In the case of traditional phenomenology, its dictum of “fidelity to experience” has a tendency to function in a same way as the creed of objectivity. Even if researchers were able to come to understand the particular phenomena of oppression and injustice, mainstream phenomenology and hermeneutics often bind researchers with their doctrine of fidelity to phenomena and the knowledge that is attained through it. It can turn researchers into mere passive observers; that is, to witness oppression and describe it as it is.

Mario Savio, spokesperson of the Free Speech Movement in the 1960’s (San Francisco Bay Area Television Archive, 2012) reminded his audience that when a university administration or any opponent to free speech calls students who are engaged in the movement, “revolutionary,” they are failing to see that what these students are supporting is the traditional idea of university and that actually those who attack this idea are the ones who are radical and departing from tradition. He explained how a university was traditionally regarded as a community where scholars, faculty, and students come together with honesty and hard work to freely inquire about important matters of science as well as social issues and engage in the question of how the world is and what it ought to be.

Upon gaining critical knowledge of the situation, critical hermeneutics and phenomenology allow us to engage with the question of what ought to be and to critically interpret and assess the observed phenomena in a way that addresses and fills the gap between the world as it is and what it should be.

What enables researchers to make this interpretation of phenomena that lead to transformation is an awakening of moral imagination. This comes from researchers claiming the subjective domain that could discern what is right and just and connecting with something often considered taboo in conventional research under the creed of objectivity.

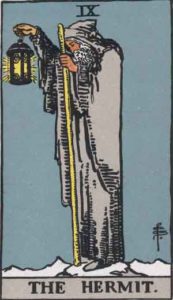

The image of Hermit depicted in Meditations on the Tarot published anonymously embodies the path of phenomenology.

Hermit’s Lamp, Mantle and Staff:

“The Hermit who haunts the imagination of ‘young’ youth, the Hermit of legend and the Hermit of history was, is, and always will be the solitary man with the lamp. For he possesses the gift of letting light shine in the darkness –this is his ‘lamp’; he has the faculty of separating himself from the collective moods, prejudices and desires of race, nation, class and family –the faculty of reducing to silence and the cacophony of collectivism vociferating around him, in order to listen to and understand the hierarchical harmony of the spheres –this is his ‘mantle’; at the same time he possesses a sense of realism which is so developed that he stands in the domain of reality not on two feet, but rather on three, i.e. he advances only after having touched the ground though immediate experience and at first-hand contact without intermediaries –this is his ‘staff’” (Anonymous, 1993/1985, pp. 200-201).

Nightflying:

Writer and poet Aurora Levins Morales (1998) describes in Medicine Stories the knowledge conquered by Western rationality with the example of witch prosecutions. This knowledge she described as “night-flying”, one of the accusations brought against witches, also captures the sight involving phenomenology. Morales elucidates night-flying as “the ability to change shape or endow a household object, a pot or broom, with magical powers and soar above the landscape of daily life, with eyes that can penetrate the darkness and see what we are not supposed to see. She continued saying how “from these forbidden heights one can see the lines of extinct roads and old riverbeds, the designs made by private landholdings, the relationships between water and growth, and the proximity or distances, between people. Those who can see in the dark can uncover secrets: hidden comings and goings, deals and escapes, the undercover movements of troops, layers of life normally conducted out of sight” (p. 49).

Researchers who engage in critical phenomenology look back at history to restore the past that has been forgotten and reveal what is concealed. In this, the force that conceals the original events is experienced as oppression and is often behind historical colonization. Phenomenological inquiry is used as a way toward the liberation of being and recovery of our memory; to decolonize and bring justice to the image that has been conquered.

References

Anonymous. (1985). Meditations on the tarot: A journey into Christian hermeticism. (R. A. Powell, Trans.). Element: Brisbane, Australia. (Original work published 1993)

Morales, A. L (1998). Medicine stories: History, culture and the politics of integrity. South End Press: Cambridge, MA.

Kearney, R. (2004). On Paul Ricoeur: The owl of Minerva. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Prilleltensky, I., & Fox, D. (1997). Critical psychology: An introduction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

San Francisco Bay Area Television Archive. (2012). Mario Savio, Jack Weinberg & free speech movement victory. Retrieved from https://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/209401

van den Berg, J. H. (1972). A different existence: Phenomenological psychopathology. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.